Creativity involves putting your imagination to work and seeing things differently!

Distinctive imaginations exist among all of us. Creativity makes the ordinary distinctive, seeing things in a new way. Multiple meanings, possibilities, experimentation, and childlike freshness may arise to the surface when tapping into the subconscious.

Last month I traveled to a metro Denver high school and discovered Creativity from the Shadows: marginalized kids participating in a presentation that explored childhood disabilities.

The teachers and the program director of this adventure captured my heart. One teacher started crying after her kids made their presentations. She excused herself from the room.

Last month I traveled to a metro Denver high school and discovered Creativity from the Shadows: marginalized kids participating in a presentation that explored childhood disabilities.

The teachers and the program director of this adventure captured my heart. One teacher started crying after her kids made their presentations. She excused herself from the room.

I had been selected to be a judge on a panel that would evaluate and critique the art/storyboards of disabled students enrolled in grades 9-12. This particular project was part of STEM, an acronym for science, technology, engineering, and math all integrated into a school program based on real-world application. The students consisted of teams of two to five kids working together through storytelling and production of a book to reveal a disability and to incorporate a character with that disability.

The director told the judges beforehand that the students came from trailer parks, from being homeless, and from E.S.L. learning groups—some of the most environmentally, physically, and emotionally challenged kids would be present. Some would be dressed in their best outfits, having picked out a favorite from perhaps three or fewer that they may own. They had worked very hard for this event and were anxious to make a good impression.

The director told the judges beforehand that the students came from trailer parks, from being homeless, and from E.S.L. learning groups—some of the most environmentally, physically, and emotionally challenged kids would be present. Some would be dressed in their best outfits, having picked out a favorite from perhaps three or fewer that they may own. They had worked very hard for this event and were anxious to make a good impression.

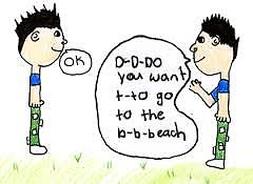

Spirited teams represented instances of cerebral palsy, dyslexia, depression, and stuttering. I marveled at their showing exuberance, creativity, and intellect. A judge could question any team member and listen to answers explaining how they interacted and characteristics of the disability. I took the chance to get to know these kids.

The presentation set-ups included tables with a display area for each team’s drawings and research material. Each judge would visit an area then grade the team based on its oral presentation, materials used, effort and the final product, usually a spiral-bound booklet.

The presentation set-ups included tables with a display area for each team’s drawings and research material. Each judge would visit an area then grade the team based on its oral presentation, materials used, effort and the final product, usually a spiral-bound booklet.

I began by visiting a team who chose stuttering as a subject. I selected one young boy, an outgoing leader who appeared eager to tell his story, and asked him, “Why did you choose this subject?” He said that he has a brother who stutters.

“Does it embarrass you?” I continued.

“Nah, he’s a great kid.” he replied. One paper pinned to their display showed the slow repetition of consonants: th, th, th, the and sh, sh, sh.

I visited the next two-member team who chose to write about dyslexia. “Explain to me what you have here,” I requested. “Do either of you have dyslexia?”

“She does,” a beautiful petite Latina girl said, nodding to her partner—a little girl in a pink dress, on the other side of the display.

“Tell me about it,” I said to the little Latina girl.

“Well it’s not being able to finish math problems or sentences completely,” she related. The two girls had put together a beautifully illustrated book showing their relationship—how one could befriend another having a disability.

Next, I approached a group of four cheery students. One girl, smiling ear-to-ear, has a condition called “trichotillomania.” This disorder is an irresistible urge to pull out your hair. The smiling girl was partially bald. She said she doesn’t pull at her hair during meal time—like at the cafeteria—because “it’s too gross.” I asked, “Have you thought of wearing a hat?”

“No, it’s not comfortable,” she replied. This effervescent young person was the team’s leader. She has been pulling out her hair since she was four years old.

I found a solo presenter, a young man with dark-framed eyeglasses. He was dressed in black and wearing a blue tie. On his display were scattered papers portraying black and dismal colors: one was of a boy sitting on his bed in a bedroom; “there is no one at home to help him,” the young man remarked, mustering up such a quiet, simple, heartrending defense of his project that I had to shift my eyes to the next image. As the mother of an artistic, solo son, I resonated with so much loneliness in one so young. The picture showed a bold circle representing a rug and there was a chest of drawers with a lamp and its cord on top. Dark black streaks were the focal point of his pictures. Some crudely drawn illustrations lay on the display table. There was no finished product—no book. This presenter and a few others in the room brought with them the backdrop of their shaky environments and coping issues.

Sometimes we do not realize the behind-the-scene activities that go on in our society. We are not aware of the school programs that help all of our young citizens. The activities that give kids a chance to shine, to be heard, to be positively noticed even though everything in their lives may seem negative. God bless the educators who are there to give general support, to advance the disabled kids, to give structure and encouragement to their creativity, to offer them bright drawing colors.

I am so privileged to have been selected as a part of their audience, even though it was only for one afternoon. I graded high. I couldn’t help but be buoyed in spirit by the kids’ enthusiasm. Their storyboards tell more than just about the creation of new books. The underlying illustrations, story lines, all whisper silently of the children’s individual situations as treated by family, friends, and society.

Shadows are only shadows before they talk and share.

“Does it embarrass you?” I continued.

“Nah, he’s a great kid.” he replied. One paper pinned to their display showed the slow repetition of consonants: th, th, th, the and sh, sh, sh.

I visited the next two-member team who chose to write about dyslexia. “Explain to me what you have here,” I requested. “Do either of you have dyslexia?”

“She does,” a beautiful petite Latina girl said, nodding to her partner—a little girl in a pink dress, on the other side of the display.

“Tell me about it,” I said to the little Latina girl.

“Well it’s not being able to finish math problems or sentences completely,” she related. The two girls had put together a beautifully illustrated book showing their relationship—how one could befriend another having a disability.

Next, I approached a group of four cheery students. One girl, smiling ear-to-ear, has a condition called “trichotillomania.” This disorder is an irresistible urge to pull out your hair. The smiling girl was partially bald. She said she doesn’t pull at her hair during meal time—like at the cafeteria—because “it’s too gross.” I asked, “Have you thought of wearing a hat?”

“No, it’s not comfortable,” she replied. This effervescent young person was the team’s leader. She has been pulling out her hair since she was four years old.

I found a solo presenter, a young man with dark-framed eyeglasses. He was dressed in black and wearing a blue tie. On his display were scattered papers portraying black and dismal colors: one was of a boy sitting on his bed in a bedroom; “there is no one at home to help him,” the young man remarked, mustering up such a quiet, simple, heartrending defense of his project that I had to shift my eyes to the next image. As the mother of an artistic, solo son, I resonated with so much loneliness in one so young. The picture showed a bold circle representing a rug and there was a chest of drawers with a lamp and its cord on top. Dark black streaks were the focal point of his pictures. Some crudely drawn illustrations lay on the display table. There was no finished product—no book. This presenter and a few others in the room brought with them the backdrop of their shaky environments and coping issues.

Sometimes we do not realize the behind-the-scene activities that go on in our society. We are not aware of the school programs that help all of our young citizens. The activities that give kids a chance to shine, to be heard, to be positively noticed even though everything in their lives may seem negative. God bless the educators who are there to give general support, to advance the disabled kids, to give structure and encouragement to their creativity, to offer them bright drawing colors.

I am so privileged to have been selected as a part of their audience, even though it was only for one afternoon. I graded high. I couldn’t help but be buoyed in spirit by the kids’ enthusiasm. Their storyboards tell more than just about the creation of new books. The underlying illustrations, story lines, all whisper silently of the children’s individual situations as treated by family, friends, and society.

Shadows are only shadows before they talk and share.

The Longmont Times Call published a similar version of my story:

LaVelle, Betty (2015, June 22). Creativity from the shadows [Guest Opinion]. Longmont Times-Call, p. 4A.

LaVelle, Betty (2015, June 22). Creativity from the shadows [Guest Opinion]. Longmont Times-Call, p. 4A.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed